We happened to visit Arles at Easter weekend, just in time to experience the festivities of La Feria, the fair, with a highlight being La Corrida, the bullfight. Each day of La Féria de Pâques, Arles has a running of the bulls before and after the bullfight. Heavy barriers are erected along the blocked-off section of street, but this doesn’t stop large numbers of pedestrians from stepping inside.

This is not like Pamplona where the large bulls that will fight in the arena are transported to the site. Instead smaller bulls are brought to run through the street one at a time for entertainment. Large white horses race back and forth multiple times on the route, five or six at a time. The bull is completely surrounded by the horses, so much so that it’s difficult to even see it.

This is what the horses look like as they race by. And yes, Michael was standing inside the barrier as he took this shot.

Young boys race after the cluster of animals, trying to grab the bull or its tail. The likelihood that the bull will escape is low, but the likelihood of being trampled by a horse is higher. Nevertheless, some of the kids were successful, bringing the bull to the ground…and ending up with manure-soaked shirts and bragging rights.

We weren’t quite sure what to expect inside the arena; some bullfighting is ceremonial, with non-fatal engagement between matador and bull. Spoiler alert: Not so in the bullfighting of Arles. There will be blood.

Arles is a very old city in Provence, established in 800 B.C. and taken over by the Romans about 100 B.C. Roman influence is very visible in the city’s architecture, notably the arena where the bullfighting takes place. Its arches are a bit Colosseum-esque.

Built in 90 A.D. the arena once hosted chariot races and gladiator battles (to the death). Now it has bullfights (also to the death).

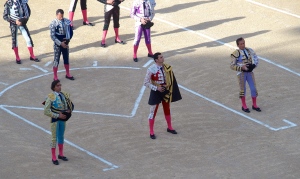

The arena holds about 20,000 people, many seated on the same stone seats put in place in Roman ages. The audience is on the edge of these seats to see the excitement of the bullfight. La Corrida (Spanish for bullfight or run) takes place over four days. Red-jacketed band members play rousing songs, including Bizet’s Toreador Song from the opera, Carmen.

Among the matadors for the event we watched, Perez is only 24 years old while Frascuelo is 67.

After the processional beginning, the bullfighting gets down to business. A bull is released to run around the arena. These are not roping calves, but big muscled beasts with long sharp horns.

Junior matadors step out from behind barriers and shout taunts to attract the bull to all parts of the giant field. A 1,000-pound bull can use a lot of energy running wildly for five or ten minutes. During this time, the bullfighters look a bit like circus clowns running around the outside of the ring and jumping behind the barriers.

This bull is lively, angry, and brave, holding his head up proudly. If the matadors didn’t have the barrier to hide behind, they would be toast!

Soon the junior matadors venture farther out from behind their barriers. They use their large magenta and yellow capes to engage the bull to make a pass. The intent of this taunting and passing is to determine how brave the bull is. Sometimes the matadors themselves will participate in this phase so that they have first-hand impressions of the bull before they engage one-on-one.

A bugle sounds and the first phase begins. A picador on horseback comes out with a long lance. His objective is to stick the point in the bull between the back and neck. A strategic placement can cause the bull to drop his head and tire more quickly. These horses basically stand still while the picador plans his attack.

Sometimes the bull reacts quite violently, ramming head and sharp horns into the belly of the horse, thinking the horse is the cause of its pain. Now horses are equipped with peto coverings, which appear to be thick mattress pads. Through the 1920s, before the peto, the horses were frequently gored by the bulls and died. Sometimes more horses than bulls died in the multi-day events.

One picador was jolted off the horse and escaped over the arena wall. A helper in red tries to rescue the horse, disengage the bull, and avoid getting gored himself.

We wondered why the helper wore red when he jumped into the arena to rescue the horse. Wouldn’t his red shirt attract the bull? It turns out that bulls are colorblind, so red is simply a color of tradition, not one that instigates anger.

Another bugle sounds for the next phase. The bull is now tired and a bit slower. Three banderilleros hold their banderilleras in outstretched arms. They try to attract the bull and as it passes, they thrust these barbed sticks into the same vulnerable location at the back of the neck.

In the banderillero phase, the torrero may stand on his toes and make mincing moves back and forth, unless, of course, the bull is charging. Then he hopes for distracting help from the others with their magenta capes.

After the wounds to his neck, the bull can no longer hold its head up. It charges with its nose to the ground and sometimes stumbles to its knees. Nevertheless, its half ton of momentum and sharp horns are still quite dangerous.

Two banderilleras planted and four to go.

Another bugle and the matador steps into the arena alone with the bull. The matador now uses a red cape, much smaller, the better to draw the bull close, and he does so repeatedly. Perez, the youngest of the matadors we watched, demonstrated best (to our uneducated eyes) some of the art of bullfighting in drawing the bull very close and bending his upper body over the bull, sometimes with his back to the bull as it approaches.

After numerous passes, the tired bull simply has to stop to catch its breath. Then the matador turns his back on the bull and steps slowly away. Hemingway, who became a bullfight aficionado, described the matador’s are in The Sun Also Rises:

| Each time he let the bull pass so close that the man and the bull and the cape that filled and pivoted ahead of the bull were all one sharply etched mass. It was all so slow and so controlled. It was as though he were rocking the bull to sleep. He made four veronicas like that … and came away toward the applause, his hand on his hip, his cape on his arm, and the bull watching his back going away. |

| — from The Sun Also Rises |

At this point, the bull is often too tired and weak from loss of blood to put up much resistance. The matador holds his sword to face the bull and draws it into one more pass. Then he sticks the sword into the bull, attempting to pierce its heart.

And then the bull just keels over with a few shudders and a collapse of its massive bulk.

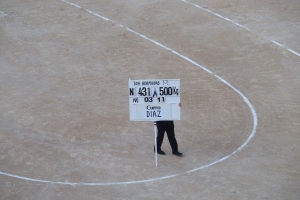

Two large horses come into the arena to pull the near-dead carcass off the field. Groundskeepers move in to clear away the blood and refresh the white markings.

Each day three bullfighters battle two bulls each, with a double set on the final day. So 30 bulls appear between Friday and Monday and 30 bulls disappear to the butcher shop.

Is this sport or art or animal cruelty? Hemingway thought it was high art. French and Spanish advocates have indicated interest in having bullfighting identified with the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage label, which would indicate the need for urgent safeguarding to be kept alive.

On the other hand, this kind of bullfighting could be outlawed in France as in other countries to keep the bulls alive. We would vote for this choice.

Ah, that answers my question about the pink vs red capes.

LikeLike

One other detail about the capes. The matador spreads it wide holding a sword across the top, purely functional. Then when he is ready to make the killing blow he switches to a sharp and shiny one.

LikeLike

How sad… I wouldn’t be able to watch that – I hope they end up outlawing it soon. As to tradition? Well, times change. We don’t have gladiator fights or bearbaiting anymore either. And cockfighting is outlawed in the U.S. Those poor animals – such senseless violence and cruelty.

LikeLike

I agree. I cried through the first fight. Then it becomes a bit like watching violence on television. It seems very sad, but unreal.

LikeLiked by 1 person